The biggest cyber heists in history: The bybit, MGM and Sony hacks - similarities, effects, damage and awareness potentials

Published Date:

- March 26, 2025

The similarities and differences are impressive – in our irregular series ‘The biggest cyber heists’, we look at the biggest cyber heists in history. Today’s post analyzes the bybit, MGM and Sony hack. We summarize what happened, how it happened, who noticed it, what damage was done and what the consequences were. We then examine what measures would have been useful to counteract this and whether something could have been done with more vigilance.

At the end, we take stock, compare the cases and consider what could have been done better. And, of course, from a cybersecurity awareness perspective. Let’s start with the most recent incident, the bybit hack from February 2025:

The $1.5B ByBit Hack 2025

In February 2025, Bybit, a leading cryptocurrency exchange headquartered in Dubai, suffered the so far largest crypto exchange hack when some cyber criminals stole $1.5 billion worth of Ethereum. The attack was attributed to the Lazarus Group, a North Korean state-sponsored cyber crime organization with a known history of targeting digital financial systems [1].

The bad guys gained access through a highly sophisticated and multi-phase operation that began with compromising the Safe wallet UI, likely via a supply chain vulnerability or social engineering. They injected a malicious script that manipulated transaction data in real-time without triggering internal monitoring systems. Specifically, the attacker embedded a `delegatecall` into the transaction logic [2], allowing unauthorized contract upgrades and redirection of funds to attacker-controlled wallets. The visual transaction data presented to Bybit’s signing team appeared legitimate, but once signed, the assets were rerouted on-chain. The hackers then initiated immediate withdrawals and obscured the funds’ trail using chain-hopping techniques. Attribution investigations confirmed the involvement of the Lazarus Group, based on behavioral and forensic blockchain analysis [1].

Bybit detected the breach during a routine transaction on February 21, 2025. Security alerts were triggered almost immediately, prompting the isolation of the compromised wallet and halting further unauthorized withdrawals. Emergency response protocols were launched within minutes [1].

The financial damage was eye watering: $1.5 billion in Ether was stolen. Despite this, Bybit remained solvent. Within 72 hours, the exchange secured 447,000 ETH in emergency liquidity from partners including Binance and Galaxy Digital, avoiding any user withdrawals suspension and stabilizing operations. Ethereum’s price dropped 24% following the breach, and Bitcoin fell below $90,000, reflecting market-wide concern [1].

Using the harm taxonomy by Bada et al. [3], the consequences can be assessed as follows:

5 – Financial Harm: Largest recorded crypto theft, immediate liquidity problem, long-term financial scrutiny.

4 – Operational Harm: Cold wallet infrastructure was temporarily disabled, and transaction approvals were reengineered.

4 – Reputational Harm: Global visibility and trust implications despite fast containment.

2 – Legal and Regulatory Harm: Expected regulatory inquiries and increased oversight, though no formal penalties announced as of March 2025.

Bybit responded with extensive structural changes. It partnered with its wallet provider to redesign its multisignature framework, added manual verification layers to sensitive processes, launched a bounty program for fund recovery, and completed a proof-of-reserves audit within three days. CEO Ben Zhou communicated transparently through livestreams and public updates to reassure stakeholders.

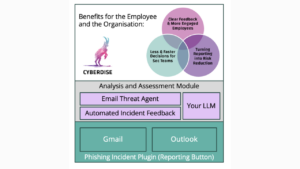

The hack was clearly aimed at the developers of the platform and our experience shows that IT departments do not have significantly better awareness ratings than the rest of the business. We find that cybersecurity awareness initiatives, including social engineering training, phishing and smishing simulations, and real-time anomaly detection for transaction approvals, could have reduced the likelihood of successful interface manipulation or alerted operators before execution. A phishing alert mechanism may have mitigated upstream attack vectors such as employee-targeted exploits.

In conclusion, the Bybit incident shows how layered defenses, immediate and competent crisis management, and financial resilience are vital in responding to state-sponsored cyberattacks against critical financial infrastructure. So, protection and recovery where fully in focus at Bybit, but what about identification and prevention?

The $100M MGM Resort Hack in 2023

In September 2023, MGM Resorts International, a global hotel and casino giant, suffered a cyberattack that significantly disrupted its operations and exposed sensitive customer data. The breach was attributed to the ALPHV (BlackCat) group, which collaborated with Scattered Spider, a group specializing in social engineering attacks [4][5].

The attackers infiltrated MGM’s network using a social engineering techniques vishing and phishing. By impersonating an employee over a phone call to the IT help desk first, they tricked support staff into providing access credentials. From there, the attackers gained unauthorized access to internal systems and deployed malware to disrupt operations. The attack originated from financially motivated threat actors believed to be based in the west, U.S.A and UK included [5].

MGM became aware of the breach on or shortly before September 10, 2023, when unusual network activity was detected and internal systems began failing. In response, the company took immediate action by shutting down affected systems to contain the threat [4].

The financial impact here was also enormous. MGM reported a projected $100 million loss in adjusted property EBITDA for its Las Vegas operations for Q3 2023, with an additional less than $10 million in direct cybersecurity response costs. [4].

We classified the incident according to the harm taxonomy by Bada et al. [3] as we did for the Bybit Hack. The consequences were as follows:

- 4 – Financial Harm: $100 million in losses plus response costs and future liabilities.

- 4 – Operational Harm: Disruption of slot machines, hotel check-in, and digital services. Watch the video showing all the slot machines down 😉 [6]

- 4 – Reputational Harm: Public and media exposure of a major breach at a leading hospitality brand.

- 3 – Legal and Regulatory Harm: Exposure of personal data including driver’s licenses, Social Security, and passport numbers for customers prior to 2019, with regulatory and legal implications.

To mitigate future risk, MGM has restored its guest-facing systems, enhanced monitoring capabilities, and launched a forensic investigation in coordination with authorities, including the FBI. It also reworked its access control processes and employee security protocols.

Improved cybersecurity awareness through regular phishing and vishing simulations, mandatory employee training, and the introduction of rapid alerting tools could have helped detect and prevent the initial compromise or reduced its extent.

The MGM breach illustrates how a single well-executed social engineering attack can escalate into a large-scale cybersecurity catastrophe and life-threatening business continuity crisis. Okay, people will always gamble…

The widely known $100M Sony Hack in 2014

In late 2014, Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE), was the target of one of the most renown high-profile cyberattacks in corporate history. The attackers, naming themselves as the “Guardians of Peace” (GOP), infiltrated Sony’s systems, stole large amounts of data, and deployed destructive malware that rendered significant portions of the company’s IT infrastructure unusable [7].

The bad guys gained access through a combination of spear-phishing emails and network exploitation. According to forensic evidence cited in later investigations, the initial access was likely achieved by tricking employees into opening malicious email attachments, which installed malware and established a foothold in the network. From there, the attackers escalated privileges and moved laterally across systems, ultimately deploying a wiper malware called Destover, which destroyed files and boot records across Sony’s Windows-based systems. U.S. authorities attributed the attack to North Korea, reportedly in retaliation for Sony’s planned release of The Interview, a satirical film about a plot to assassinate the country’s leader [8][9].

Sony became aware of the breach way too late: On November 24, 2014, employee computers displayed a message from the attackers, accompanied by a graphic of a red skeleton (like in a movie!). Simultaneously, internal systems became inaccessible, and massive data exfiltration was discovered during the forensic response [7].

Estimates of the financial damage vary, but losses likely exceeded $100 million, including costs related to investigation, remediation, legal claims, regulatory response, lost productivity, opportunity costs and other stuff [7].

Using our taxonomy [3], the harms can be classified as follows:

- 4 – Financial Harm: Investigation, legal settlements, and halted projects resulted in over $100 million in losses.

- 4 – Operational Harm: Sony’s internal systems were largely disabled for weeks, affecting productivity and halting several business processes.

- 4 – Reputational Harm: Internal emails and unreleased films were leaked, damaging Sony’s public image and industry relationships.

- 3 – Legal and Regulatory Harm: Employee lawsuits and regulatory investigations were triggered by the exposure of personal data.

After the hack Sony implemented improved access controls, revised incident response procedures, deployed endpoint detection systems, and worked closely with cybersecurity firms and U.S. law enforcement. They also reviewed its third-party risk exposure and began a long-term overhaul of its infrastructure security.

It’s clear: stronger cybersecurity awareness, including phishing simulations, employee education on suspicious communications, and tools for rapid alerting (such as a phishing report button), could likely have prevented the initial compromise or at least delayed lateral movement by alerting security teams earlier.

The 2014 Sony hack simply demonstrated what sophisticated state-sponsored actors can achieve.

Conclusion and Comparative Analysis

From my perspective, the three cases — Sony (2014), MGM (2023), and Bybit (2025) — reveal recurring patterns in cyber risk exposure across industries.

Harm/Impact on Business

- Sony: Severe reputational and operational harm with over $100M in losses and business disruption.

- MGM: Financial loss (+/- $100M), operational downtime, and regulatory scrutiny, though core operations resumed within weeks.

- Bybit: Catastrophic financial harm ($1.5B theft), but operational recovery was rapid due to liquidity support.

If you only look at these three incidents, you might get the impression that although the chances of survival have increased over time, there is still huge damage and losses. But to draw such a conclusion from these 3 cases would be very unserious in any case.

Threat Actors and Access Methods

- Sony: State-sponsored (North Korea), access via spear-phishing and internal exploitation.

- MGM: Social engineering by Scattered Spider Group, posing as staff in IT helpdesk calls.

- Bybit: Lazarus Group, exploiting wallet infrastructure via code injection and possible supply chain compromise.

Could It Have Been Prevented with Better Cybersecurity Awareness?

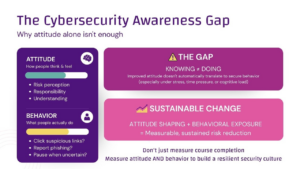

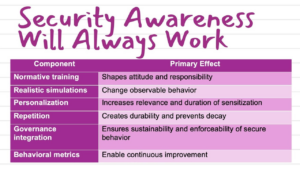

In our view, yes. All incidents involved an element of human manipulation or overlooked security behavior. Enhanced awareness, phishing/vishing detection training, and real-time alert mechanisms could have disrupted attack chains early and substantially limited impact.

We still see that most companies are practicing cybersecurity awareness. However, this is often not always done in the best way. Almost no CISO champions the much-needed motto “Awareness for Cybersecurity Awareness!”. – As Simon Sinek said: Start with why! [10]

So Long, Palo Stacho

References

[1] https://cointelegraph.com/learn/articles/how-the-bybit-hack-happened

[3] Taxonomy: https://academic.oup.com/cybersecurity/article/4/1/tyy006/5133288 and harm rating by the authors: 0 – No Harm: No discernible impact; operations and business continuity remain fully intact. 1 – Minor Harm: Negligible impact; no disruption to business continuity. 2 – Moderate Harm: Limited impact; business continuity is partially affected, but core operations remain functional. 3 – Substantial Harm: Significant impact; business continuity is noticeably disrupted, with reduced operational capacity.4 – Severe Harm: Major impact; widespread disruption to business continuity across multiple functions. 5 – Catastrophic Harm: Critical impact; business continuity is compromised and the organization’s operational viability is at risk.

[5] https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-66803401

[6] Youtube – MGM Slots down: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uh9Tyz9X3Vo

[10] Youtube – Simon Sinek TEDxPugetSound “Start with why” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4ZoJKF_VuA&t=9s